The Multicellular Origin of Cancer and the Evolution of Oncogenesis: Part 8

PART 8: Metastasis is not quite a scheduled end of the Oncogenetic Evolution

The epic journey of oncogenesis is an evolution that is not programmed to end with metastasis. Could a terminally ill human body with an aggressive metastatic tumor somehow be able to live on, the oncogenetic evolution would have continued with tertiary, quaternary and quinary tumors, and so forth. But hardly living their “secondary” stage of multi-generations, almost all tumors prematurely see the end of their evolvement, passing away along with the organisms they kill.

A primary tumor’s genomic instability persists in metastasis not just frequently [5] but always. The sequence of the growth advantage metastatic cells gain through accumulated mutations takes place with the same means and mechanisms as the ones we see with primary tumors. In the microenvironment of a metastatic tumor, with some exceptions, most of the conditions of the neoplastic progression are identical with the ones seen in the primary tumor’s microenvironment. In metastatic tumors, we see the same consequences of being a solitary cell exactly as the ones in primary tumors.

The selective pressures and conditions of the changing environment and immune system with warrants and sanctions ultimately define the fittest of the outcompeting cell groups. As conventionally agreed upon, it is the survival of the strongest. But, contrary to another conventional opinion, it is not “every cell for itself”. Just like the primary tumor’s own environment, the territory of the metastatic neoplastic progression is a platform where metastatic cells’ destinies are determined as either dormant state or tumor progression, or apoptosis. As one of the striking main features of metastatic tumors, the genetic heterogeneity of metastases reflects heterogeneity already existing within the primary tumor which is a mixture of numerous subclones each of which has independently expanded to constitute a large number of their own cell groups [6].

While the tissue’s healthy cells together act as a microenvironmental control system to prevent the development and progression of emerging tumor cells [7], all the cells without exception get variably involved in the countless molecular and biomolecular transactions and alterations by which they all get their development, prosperity, maintenance and affluence effected one way or another. The responsibilities, obligations and liabilities carried out by the overseeing tissue governance in metastases are exactly the ones that are observed in the primary tumor’s microenvironment. Just like the way it happens in the primary tumor microenvironment, a metastatic domain can in no way allow any exception for any particular cell within the territory. So, just like the primary tumor’s microenvironment, the microenvironment of the metastatic tumor executes the same strict rules which no cell can overcome solitarily.

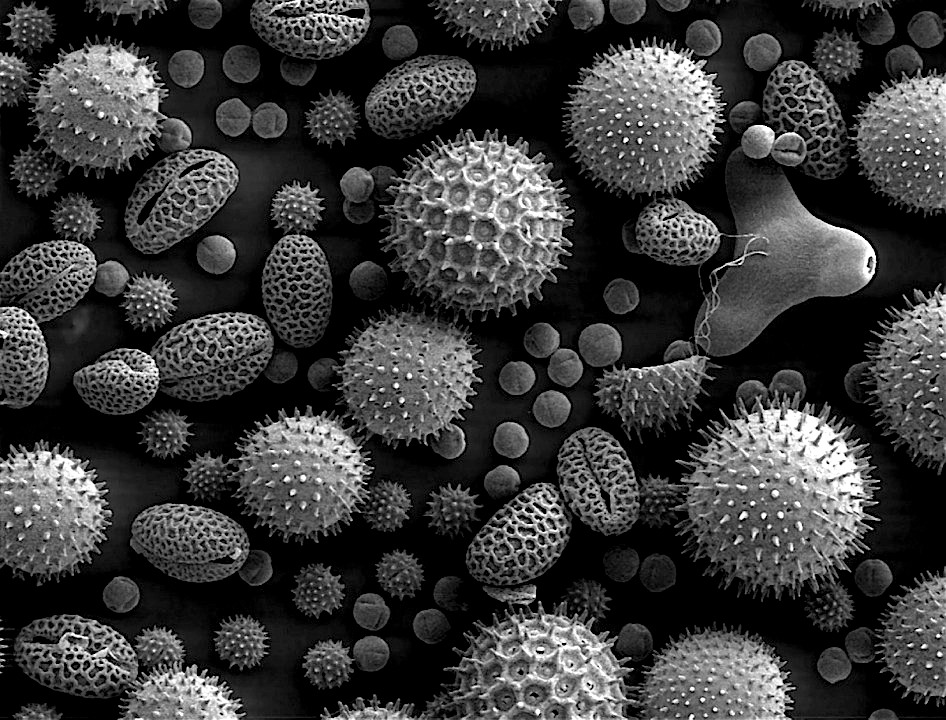

Through the evolutionary process of neoplastic tumors, the natural selection leans on phenotypic variability generated by the accumulation of genetic, genomic and epigenetic alterations [8]. The deriving productive aggressive phenotypes, however, take quite a time to take hold. With an average doubling time of 20-40 hours [9], newly produced cancer cells are basically not robust enough to live their younger days successfully in terms of survival, and most of them die before they can manage to carry out their own divisions, which is the reason it takes some time for any primary or metastatic tumor to fully establish itself as equipped to the hilt. This reflects the fact that the pursuance of neoplastic formation, both primary and metastatic, is an affair of clonal expansion with clonal selection, and ultimately a matter of clonal wars where solitary cells of commitment, ascendancy or eloquence have yet to conform to integrate or get doomed to destruction.

By having mutations shared by no other cells, solitary cells lose their fight for survival as soon as the fact that they are limited in the long term to fully meet the conditions to fit in becomes apparent and gets discovered by the regime to which the solitariness is nothing more than redundant presence within the multi-power, multi-pressure and multi-liability commune of integral significance and values which is in an ongoing state of conflict and clashes for differences to equalize and exchanges to compromise.

Cancer cells’ genotypical, phenotypical and biological heterogeneity, which collectively brings intraclonal and microenvironmental mechanization and mobility, is directly proportional to their ultimate individual and colonial invasiveness and metastatic ability both in primary tumors and metastases. In order to live with a guaranteed future in a metastatic niche, disseminated cancer cells should land there in clusters or in assembling groups, not necessarily at the same time, but within a certain short period of time.

Just grouping, however, to have a decent settlers life, is not sufficient; in addition to the abilities they have, they should generate and acquire capabilities that are necessary to confront and overcome the new barriers of the unpermissive microenvironment while organizing themselves to form an aggressive colony. Their fate mainly depends on their own qualities and capabilities while, in part, they are under the effects of microenvironment’s signaling system to which they principally do their best not to succumb.

If a metastatic cancer cell lands in a new location solitarily and remains so for 12-18 hours without having a chance to perform reproductive activity, it becomes dormant or undergoes apoptosis. If a solitary metastatic cell is the only tumor cell that has landed in a distant tissue site, whatever productive and aggressive capacity and capability it may have, it will be forced to dormancy or apoptosis. Should it be quick and smart enough to keep the control and pressure mechanisms of the microenvironment busy and therefore earn time to go into mitosis, which is its only goal anyway, its daughters, the ones which would be more difficult cells for the microenvironment’s governing power to suppress, would in fact be the problem the microenvironment is intimidated by. That’s why, under normal circumstances, that would not be the case as the indisputable power of the microenvironment would not allow such a trivial settlement to become a threat.

If two or more solitary metastatic tumor cells land in a distant tissue site together at the same time or in succession and close enough to each other, they engage in communication using their exosomes. Unless they become dormant or undergo apoptosis, they quickly team up to flourish and multiply to create a micrometastasis. But reaching their goal is not easy if they are from different clones of a primary tumor, and their chance of achievement is the highest if most or all of them come from the same clone which is extremely unlikely.

Different-clone cells have a tough time equilizing their geno-phenotypical differences while at the same time they both make their best efforts individually to communicate with the watchful microenvironment to convince it to sanction and even cooperate. Their presence as newcomers with their swiftly emerging dynamism of both individualism and group-conflict immediately becomes difficult for the uncooperative microenvironment to deal with, and the required “host measures” emerge to eliminate them by forcing them to dormancy or apoptosis.

The cells of a multi-clone group can get away only when they manage to equalize their differences via their communication which not only conflicts in itself, but also gets disrupted by the microenvironmental forces. Same-clone cells, on the other hand, whose running into each other is mathematically less likely than that of different-clone cells, would be more concurring to team up, more powerful to flourish and more convincing to get the microenvironment’s acquiescence.

For the flourishing metastatic group cells, establishing micrometastasis is not a guarantee for a bright future as every new generation becomes more ineffectual than the preceding one. In a “Limited Survival of Early Micrometastases” study titled “Multistep Nature of Metastatic Inefficiency”, Luzzi and his colleagues [10] neatly demonstrated that metastatic inefficiency is principally determined by two distinct aspects of cell growth after extravasation: Failure of solitary cells to initiate growth and failure of early micrometastases to continue growth into macroscopic tumors.

Copyright © 2014-2016 M. M. Karindas, MD